If you are learning about the Anunnaki, two names you are going to hear a lot are Enki and Enlil. While there are a number of “central characters” in the myths and legends of the Anunnaki, much of the action revolves around these two sibling rivals.

In this article, I am going to give you a crash course in the mythology of Enki and Enlil. But this is a complex topic, and I do not want to jump into it without laying the initial groundwork. So here are the absolute basics, just in case you are brand new to learning about the Anunnaki.

When we talk about the Anunnaki, we are referring to the ancient gods of Mesopotamia. But depending on who you ask, the Anunnaki may also have been alien visitors from a planet called Nibiru which is in a long orbit around the sun.

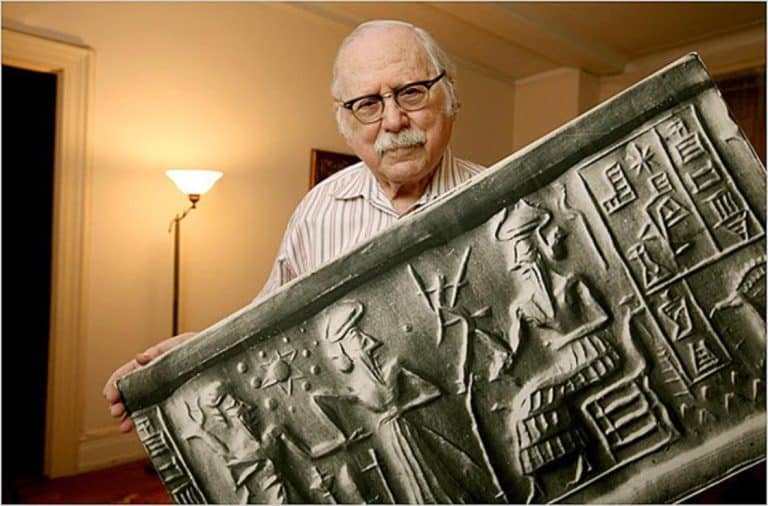

Naturally the space alien theory doesn’t fly in the mainstream, but it was popularized by a Russian-born American author named Zecharia Sitchin. Since he presented his ideas to the world, they have become a recognizable fixture in popular culture.

I will be talking more about Sitchin and his ideas later, but first I want to get back to Sumerian mythology. I am going to introduce you to Enki and Enlil and their place in the Mesopotamian pantheon, and then I will tell you how they figure into the ancient flood legend. I will describe how they inspired other mythologies and religions, including Christianity.

The Sumerian Pantheon and Creation Myth

As with many other polytheistic religions, the Sumerian pantheon consists of a number of gods who are all related to one another.

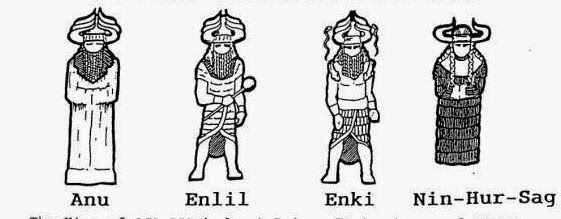

It is easiest to describe the shape of this family tree by starting with Anu. Anu is also known as “An,” the Great Father of the Sky. He is the original supreme deity in the pantheon, lord of all the other gods. He loses this position as the Sumerian tale unfolds, passing it off to Enlil and then (in Babylonian lore) to Marduk.

You will notice that Anu is not the first god in the family tree.

His parents are two primordial gods, Anshar and Kishar. If you happen to be versed in Greek mythology, you can think of these primordial gods as being a little bit like the titans who preceded the ancient Greek gods. After the Greek gods overthrew the titans, the importance of the titans took a backseat to the significance of the gods (in general).

The same is true here—the primordial gods factor into the creation myth of the Sumerians, but are less important later on.

Returning to Anu, Anu’s two consorts are Antu, Great Mother of the Sky, and Ki, the Earth Mother. Both gave him children.

- Ki gave birth to Enlil, Lord of the Air and Earth, Guardian of the Tablet of Destinies (to start), and Nin-khursag, Lady of the Mountain.

- Antu’s child was Enki, Lord of the Earth and Waters, known also as “Ea.”

As you can see, Enlil and Enki are half-brothers. Following his birth, Enlil cleaved the earth from heaven. At this point, he and Ki took command of the earth, while Anu continued to reign in heaven.

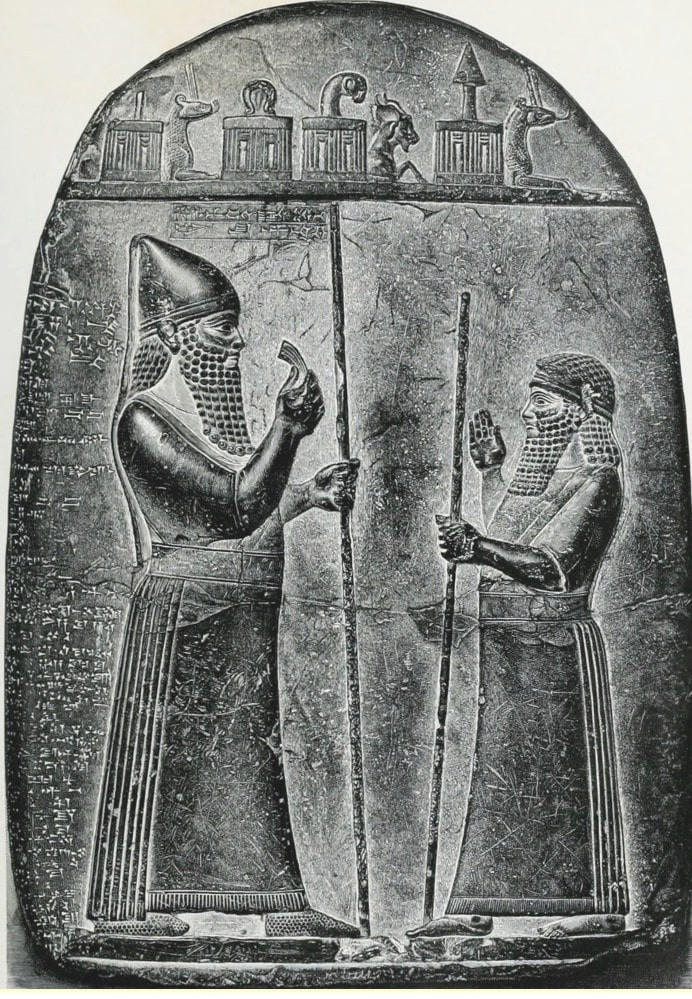

What is the Tablet of Destinies?

Just now I mentioned Enlil as the “Guardian of the Tablet of Destinies.” This is a mythological object of supreme importance. It is quite literally supposed to be a clay tablet engraved with cuneiform. Whichever god possessed it was considered the ruler of the universe.

Note that “Tablet of Destinies” is the proper name for this object. People often get it wrong. You may see it incorrectly referred to as the “Tablets of Destiny.” It is a singular object. I have also seen it called the “Table of Destiny.” I have no idea what is up with that.

In any case, according to many texts, Enlil was in possession of the Tablet for a long time, which made him supreme ruler of the universe, surpassing even Anu. There is however a Sumerian poem titled “Ninurta and the Turtle” which mentions that Enki possessed the Tablet.

The Tablet changes hands a number of times, depending on the text you read. At one point, Tiamat, the Dragon Queen (look for her at the very top of the family tree), possesses it. She gives it to her consort Kingu, who becomes commander of her army. Marduk, Enki’s son, beats Tiamat in single combat, then defeats Kingu, claiming the Tablet and the authority for himself. At that point, Marduk becomes supreme ruler.

Just to complicate matters, this whole tale with Marduk only shows up in the Babylonian version of the myth. In the Sumerian version, Enlil beats Tiamat and reigns supreme.

Genesis of the Flood Myth

Yes, I deliberately titled this section “Genesis of the Flood Myth”—not “The Flood Myth of Genesis.” If you have read anything about Anunnaki in the Bible, you likely knew I was going to get around to this. This is where a lot of the stories of the Anunnaki converge. And as you may also have guessed, Enki and Enlil are key players.

The Judeo-Christian Version:

Many people are familiar with the flood myth in the Bible. This is the story of Noah’s Ark. The summary version is that Yahweh was getting fed up with the sins of humankind. More specifically, He was upset about the corruption of mankind by beings referred to as the “Nephilim.” Consider this passage from The Book of Jubilees, 7:21-25:

“21 For owing to these three things came the flood upon the earth, namely, owing to the fornication wherein the Watchers against the law of their ordinances went a whoring after the daughters of men, and took themselves wives of all which they chose: and they made the beginning of uncleanness.”

It is quite easy to equate the “Watchers” or “Nephilim” with the Anunnaki.

I urge you to read up on this topic in detail in my article “Who Were the Nephilim?” Basically, fallen angels brought science and technology to humanity, but did it to enslave and corrupt them. Interbreeding ensued, leading to a race of demigods.

Yahweh decided to wipe out everyone and start over.

So He told Noah to build a great Ark. Noah loaded up the Ark with two of every animal and put his own family onboard. The flood destroyed all animal and human life outside the Ark—as well as (presumably) the fallen angels and Nephilim. Noah’s family were able to repopulate the earth after they disembarked. God put a rainbow in the sky as a promise He would never judge the earth again with another flood.

The Sumerian Version:

The Sumerian flood myth is older than the one in Genesis, which is why I asserted with my title that the Sumerian story is the genesis of the Bible flood myth. This belief is shared by many scholars. It is thought that a number of early ancient Hebrews were in fact inhabitants of Mesopotamia.

This would have enabled them to pick up on the Sumerian myths and legends and use them as a basis for their own religion.

There are a number of Sumerian texts which feature a great flood in one form or another. The earliest known example is in the Epic of Ziusudra. Others include the Epic of Atrahasis and the well-known Epic of Gilgamesh.

The Epic of Gilgamesh is the story which bears the strongest resemblance to the later Genesis version featured in the Bible. Interestingly enough, it doesn’t seem to have been originally included in the tablets; it was edited into Tablet XI later by someone who was inspired by the Epic of Atrahasis.

I will tell you more about Gilgamesh in a moment, but first I want to briefly talk about the Eridu Genesis.

The Eridu Genesis was discovered on a fragmentary tablet by historian Thorkild Jacobsen. This is how we learned the Sumerian creation myth which I have already shared in part with you.

Because the tablets are fragmentary, bits and pieces of the story are missing. In the beginning, we find that Anu, Enlil, Enki and Nin-khursag have created human beings.

There is then a missing section. Following that, we find out that a major destructive flood is on its way, and the pantheon has decided not to warn humanity or do anything to save them.

Enki decides he isn’t okay with this, so he warns a hero and tells him he should build an Ark. In the Eridu Genesis, this hero is Atra-hasis. In the better-known Epic of Gilgamesh, it is Utnapishtim.

Obviously the stories of Enlil and Enki are woven deeply into the fabric of Sumerian legends. These two played a role in numerous different aspects of the mythos. There are many ways that I could approach this discussion, but I have decided that the simplest way to organize the information would be to write a summary on each. While I could simply tell a detailed chronology of events, I personally find it easier to remember information when it is presented in relation to specific characters.

Enlil: Humanity’s Oppressor

Enlil’s role in Sumerian mythology can be summed up with reference to humanity in one word: oppressor.

Enlil was actually the god who (according to the Atrahasis-Epos text) originally commissioned the creation of the human race.

You might think that would be a good thing, but the only reason he wanted human beings was so that he would have a race he could enslave to do his bidding.

In fact, this was itself a bid for power among the gods. In the Sumerian myth (not the Babylonian one, which involves Marduk, as discussed earlier), a number of the gods are on strike because they are tired of maintaining creation.

Enlil proposes that he will solve the issue of the strike if he is named supreme ruler of the gods. In this version of the story, it is he (not Marduk) who subdues Tiamat.

Later on, Enlil becomes tired of humanity’s “noise,” and as a result, decides to kill them all with the great flood. As the god of weather, this was easy for him to do.

This then brings us full circle back to the story of Utnapishtim from the Epic of Gilgamesh, who was saved by Enki and corresponds to Noah in the Judeo-Christian version of the myth.

Amusingly enough, Enlil eventually gets over his anger after the flood and decides to make Utnapishtim immortal.

Enki: Humanity’s Champion

Now let’s talk about Enki, Enlil’s half-brother. Enki’s role can be summed up as humanity’s creator and champion.

While Enlil is battling with Tiamat, Enki is missing the whole thing, because he is asleep. Thankfully, his mother Antu, also known as “Nammu,” is able to communicate with him. She says:

Oh my son, arise from thy bed, from thy (slumber), work what is wise, Fashion servants for the Gods, may they produce their (bread?).

Enki wakes up and suggests the creation of a slave race—humanity. Now, you might think this made it his idea, but in truth, it was Enlil’s. Enlil was the one who spoke to Nammu, who then suggested the idea to Enki.

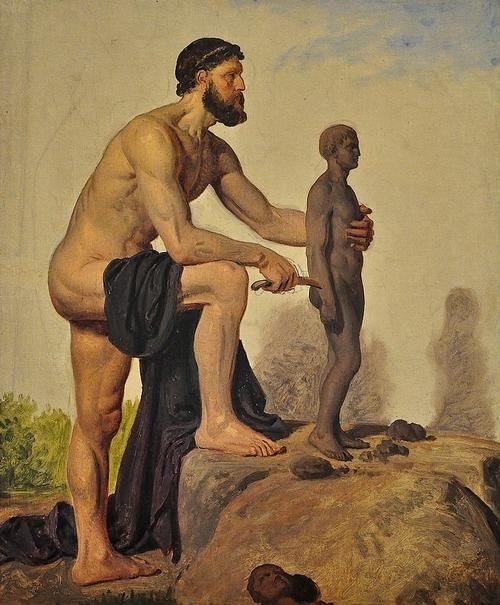

Enki himself creates human beings out of a mixture of clay and the blood of the slain god Kingu.

If you are knowledgeable about Greek mythology, this probably will ring a bell—Prometheus, the ancient titan, created humanity out of clay. The two function as very similar figures. Like Prometheus, Enki tends to stand up for the human race in conflict with the gods.

Coming back around to the flood story, Enki wasn’t too pleased when he discovered Enlil planned to wipe out the race he’d created.

So he took it upon himself to warn Utnapishtim. He told Utnapishtim to construct an Ark.

Like Noah, Utnapishtim was commanded to load the Ark up with animals. Together with his wife, he preserved life on earth when the flood was unleashed.

After the waters began to recede, he released the animals to repopulate the planet. As I mentioned previously, Enlil eventually got over his outrage and granted immortality to Utnapishtim and his wife.

The Extraterrestrial Version of the Flood Myth:

You now know the Sumerian and Judeo-Christian versions of the creation and flood myths.

The modern extraterrestrial version was popularized by author Zecharia Sitchin in volumes such as The Lost Book of Enki.

The idea is this: the Anunnaki weren’t gods, or weren’t just gods—they were alien visitors from outer space. You have probably heard Arthur C. Clarke’s famous quotation, “Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.” This is the underlying assumption in equating the Anunnaki with aliens.

If ancient humans encountered beings from another world, they would describe them in a language which made sense to them at the time. As they did not have the word “aliens,” they would simply go with “gods.”

There are numerous parallels and arguments which Sitchin and other Anunnaki alien theorists draw across the texts. There is no way to sum it all up here (I suggest checking out the rest of the articles on our site), but here are a few key pointers:

- The Anunnaki come from the planet Nibiru.

- They came to earth to mine gold, which they require to power their civilization. They created and enslaved humanity to do the hard work for them.

- All the familiar players from Sumerian mythology—Enlil, Enki, Anu, Marduk and the rest—were actually alien administrators.

- Nibiru is in a long orbit around the sun. The last time it came close to Earth, it upset the tides, causing the great flood.

- Eventually Nibiru will return, causing another cataclysm.

Those in the mainstream view Sitchin’s work with some disdain—but I would argue that it helps to view the extraterrestrial story as modern mythology. Think about it for a moment. Even the Sumerian and Babylonian texts conflict over whatever seed of truth may have inspired them. So yes, there are some inconsistencies involving Sitchin’s alien theory—but there are inconsistencies between the ancient texts as well.

So I want to wrap this up on the same note I usually come back to with our research. I hope that you now have a much stronger understanding of both Enki and Enlil and their roles in Sumerian mythology and the Anunnaki alien mythos. You also should have a pretty good idea how this all ties into Judeo-Christian lore.

But I really hope that your main takeaway is this: Every version of every story is interpretive. The truth behind the stories is unknown. By piecing together what we learn from a range of different mythologies—both ancient and modern—we can start to imagine what the completed puzzle might look like.

All of these pieces have value, and all have something to tell us about our collective journey as humankind. This is why it pays to keep an open mind!

My theory on the how they were able to preserved so many animals into one ship or ark is that the animals didnt go inside the ark in a physical way, but it was their DNA who was preserved instead. What do you think?

I’m on board with all these comments…. mankind was corrupted by the ‘giants’ and produced the awful and massive nephilim by defiling Eve and her offspring etc.

And yes DNA animal samples in the Ark sounds possible to me, that’s a great insight 🙂

You are correct about the DNA, but my question is this. Why haven’t shown humans that they are here and that they exist.

In the only account I’ve read, which is Sitchen’s “The Lost Book of Enki”, it says Zuusudra(Noah, Uphastim) was warned by enki speaking through a wall and claiming to be the wall speaking. He told him he would find tablets with blueprints to build a watertight ship(submarine) and tell people he was ordered to go to the about and serve enki as Penzance. He was to take his family and any skilled craftsmen, healers, farmers, etc with him who wanted to come, but say nothing of the flood to anyone.

The Great Pyramid was water tight and maybe the great sarcophagus found empty inside were DNA reservoirs.

Hello,

the ark was not a boat and trying to fit every type of animals and seeds to repopulate. The ark was device of some sorts, like a Stargate, or portal. It should actually pronounce it an Arch, meaning power and electricity. Judeo-christian view was actually manipulated by Constantine in Rome in 325AD creating the nicene council, combining a text what is called the Bible/cannon. Eventually removed other important scriptures such as epistle of Jude, epistle of Thomas, epistle of Mary Magdalene, Enoch, Epic of Gilgamesh, Bel and the Dragon, Macabees, Wisdom of Solomon, Magickal Keys of Solomon. Magickal Books of Moses, ETC. Again Constantine is one of those in the pyramid in social standing on earth the help enslave humanity. Every ancient Texts/Scriptures are all connected, and throughout the world. Even in the bible there are several God names. Yahweh seem to more benevolent, and Jehovah or other names seem to be somewhat malevolent towards humanity , like sodom and gomorah and destroy humanity in those cities turning them to salt. Also in my research the Jesus is connected to Enki, and Osiris, and I can see that they are insane incarnations. Meaning the the oldest texts starts with Enki and progresses down the road to his place in Egypt and Jerusalem. I can see how this all created a galactic war for supremacy for the earth and possibly throughout the multiverses. Enlil obtained throughout Mesopotamia over the 4 rivers of eden, and Enki resides in Egypt. When you go to the accounts of Genesis in creation and casting out Lucifer and is the reptilian, you realize that this is the account from the summerian tablets, the Annunaki is an account for blood line is reptillian. Reading accounts from summerian tablets show that they want to keep humanity in fear. the Bible/cannon and Hebrew texts were a tool to create fear in the minds of readers in reverence , and the a part of chain of the pyramid lineage on earth are to keep humanity enslaved as it were created hundreds of thousands years ago and still is today. I truly believe that the Kings on the earth are the lineage from annunaki here today to keep them in check. In those tablets tell us that humanity will never be released from their, or our enslavement. Unless , we can ascend in higher realms or dimensions. Jesus was showing the apostles how to ascend with magick, alchemy, and healing working with the tree of life, sephirot.

Your DNA theory is more or less the default truth given it’s an impossibility that the millions of animals on the planet, much less the mess they’d make in the ark, could have been gathered onto one ship.

Yes, that is a very likely solution. The answer that occurred to me was that Noah could only have been instructed to collect animals that were in his geographic location; That would also make the ark account feasible. Anyway, it would not have been possible for Noah to travel the whole world and collect all the animals he encountered and bring them back to the ark, that concept is completely un feasble, and even ridiculous. Although it seems that this is how Biblical accounts are interpreted.

Your comment at the end was well spoken !When we look at the pieces of the puzzle of earths past history, it goes back much further than we have been led to believe ! The Annunaki and Sumerians might have a little more prominent role in humanities history. The Watchers/Nephilum/Annunaki/Fallen Angels/could all fall into the same category, and it would make sense. The Bible does give some account to giants on the earth in the book of Genesis. What it does not tell us ,is the history and purpose of these fallen angelic beings,except to say they took human wives which in turn gave birth to men of great renown. Could these beings be what we call Nephilum ? Or what the ancients called the Annunaki ? We can only speculate.

I am taking what you have said and examining it in relation to the Bible. First, could it be Enki demanded a following of humans. A group he could call his own , who would be faithful to him and him alone? This group is called Hebrews. Now to the Book of Revelation. Could it be that Enki will battle Enlil for posession of the earth? Why do so many humans have to die in the process? Is it because humans aren’t that important? Is it because humans are mortal beings ( created that way ) and that upon death they get their true gift…eternal life? In which case they rise up to form the army of Enki and bring Enlil down. Then after 1000 years of bondage (punishment) Enlil is released (this actually is 270,000 years or close). Enlil is given another chance (why) and then he and his cronies are smashed forever and humans live with Enki forever? Am I on track? Your articles are awesome by the way! Very simple and easy to understand, thank you so much.

I’ve only read one version of the complete(supposed) version of the events, Sitchin’s “The Lost Book of Enki”. You can actually download it free if you Google search for the pdf. It like a space opera of family funding.

To keep it brief, they needed gold to repair their dying ozone. Alalu the king, was challenged by and in a wrestling match for the throne due to his inability by Anu, his son-in-law. Losing and fearing execution he fled to earth, to find the gold needed, and and force his return to power. Hijacking a ship and nukes he made it to earth, found gold, contacted home.

To verify Alalu’s claim, Ea(meaning he of the the waters, the most brilliant of all on their world, and son of Anu by Alalu’s daughter) was sent. He verified, and a deal was made for Alalu to rule Earth while Ea set up an operation to extract gold from water. Eventually Anu visiTed, Alalu challenged for the throne and lost. He was exiled on Mars and died a year later, buried in a tomb in the Shape of his face. For his success East was made Ruler of Earth and renamed Enki(Lord of Earth).

Fast Forward….

Enki has gold being extracted from the water until the seas are empty of Gold. The hole in nibiru’s ozone started growing again. Enlil, Anu’s second son, by his first wife the queen was sent to take over and get the operation started back.

The problem arose because Alalu’s daughter was Enki’s mother and Anu’s second wife, but was the first born son and crown Prince. Then Antu, Anu’s Queen and First wife, gave birth to Enlil(he had a previous unmentioned name and wasn’t called Enlil until he was put in charge of Earth mission, his name means lord of command).

Being the first born son of the King and Queen, he was legally entitled to become crown Prince by the laws of succession and would become King of their home world. Having set up an operation on earth was a perfect solution. Enlil could have Nibiru, Enki would have Earth. But the Enlil was but in charge of the Earth operation and even Enki had to follow his orders.

Arriving with workers, he made Enki set up a mining operation in the Lower Abzu(Southern Africa) and took over Enki’s command center and house in the E.Din(Eden).

Earth was the source. Mars was a way station, Marduk, first born son of Enki, commanded that operation.

You know about the annunaki rebelling after having to dig gold from the blog, Enki creating humans, (Sitchin writes it was Enki’s idea, as his lab was in the Abzu, and spent most of his time observing the land and species there, especially intrigued by the ancestors of human of the time) as a solution to end the strikes. The first ones created couldn’t reproduce and had to be insimminated in Annunaki nurses and doctors(apparently the women were the medical pros). Using crystal beakers from nibiru to mix genes from the primitive earth beings and annunaki, he created a second group which could reproduce, but lost intelligence within a few generations. Next time he used clay pots made from Earth soil to capture the essence of the world, die his mixing and viola, you get the first successful kind of man. They first start as miners. Then as field hands, then as servants in the E.Din command center. Visiting the Command center, he sees 2 earth women and has sex with them. Those children are Adapa and Titi (Adam and Eve). Adam and even amaze everyone with how advanced they are. They are paired. Enki sends Adam to Nibiru with his son Ningishzhadda to be seen by Anu, and gives secret info only Anu must see. Anu sees Adam and Evening are Enkis children. Contacts earth to say that any children on Adam and even cannot be kept as slaves. Enlil is furious at Enki’s fornication, but must obey. Marduk is amused. Enlil demands one of Adam’s son’s(Ka-In/Cain) be trained by his son Ninurta, Marduk teaches the other(Abel). Cain kills Abel after they fight and immediately goes into wailing until Adam shows up and he confesses his crime. Marduk is furious because he believes Enlil family influence on his nephew Cain caused him to murder Abel.

Fast Forward

Children of Adam(humans) are taught crafts and skills to serve the gids as overseers of the workers(the Slave Race of Men) and keep the gold operation going.

Enki father’s many children, including Enoch and Noah.

Enlil rapes a young nurse, convicted and exiled, forced to Marry her on his return from exile.

Marduke asks permission to marry Sarpanit, a Human of Adam’s line, who’said father is a son of Enki by a Human. Enki warns him he would have his rights as a royal prince on nibiru, to which Marduk says, “I have no rights or inheritance there, and what I might have had here was taken by Enlil just like yours was taken. Mars is dying, I will marry her and if I ever rule it will be on earth, with my human family. Enki contacts Anu, it is decided he can marry her, but can never go to Nibiru again. The Igigi, Marduk’s followers who work on Mars, come to earth fir his wedding, and decide the want wives from Earth and take earth women and capture the spaceport, threatening to destroy it if they aren’t allowed their new wives. Enlil is pissed and now wants all Earth beings dead, Slave or human. He views fornication with humans as disgusting perversions, but for a prince to marry one, then his followers to threaten to rebel I’d they’re not allowed to marry them, he fears the missing is ruined and corrupted, even though gold still flows. Then the flood happens.

Enlil commands no humans be warned. Annunaki with human families can abandon them or go to mountains. Annunaki who are young can go to nibiru. Enki and Enlil can’t go home because theit lives have adjusted to earth time and they’d die ball on nibiru. Enki is told by a mysterious annunaki visitor from home to tell his son Ziusudra(Noah) by a human to build a waterproof ship(submarine) and gather as many skilled people and animals as he can and say he must go to serve Enki in Abzu as penance and will found a new city there in Enkis name. Earth floods…

Enlil discovers Ziusudra has survived, sees the ship, and is about to kill him until Enki defends Ziusudra, saying he’s Enki’s son and how the visitor told him. Enlil also met the visitor before, who no one at home can confirm exists, and takes it as a sign from fate that humans should survive.

Basically Enlil is the Hebrew God and it shows by his personality and his depictions and symbols.

Being the Enki is lord of the Earth and considered opposite or the adversarules of “God” and is the Hebrew “Satan”. Marduk, later on becomes Amen-Ra(The Unseen Bright One(Intelligence to rival Enki, who tauft him all that Enki himself knew) in Egypt. Christians call him Lucifer.

I believe this is not a myth, tis truth and I sure wish someone with authority that the people of the planet would listen to would stand up and tell the world this truth. Everyone is so brain washed that they aren’t listening instead they are laughing! Nin-Hur-Sag we need for you to speak to us!

Aho

Darwin,

I believe you are exactly correct grain and genetic materials , relative to Zechariah sitchens perspective on this matter i wpuld assume you are farmiliar with his opinion on this matter if not you should consider getting farmiliar with his info and you will at very least find it very confirming toward your own take on thus matter.

It is my assertion that Enlil was the Hebrew Yahweh not Enki. Enki was demonized in Genesis as the deciever of mankind. The serpent is Enkis symbol. The Ancient Hebrews probably considered Enki weaker than Enlil due to the fact that Enki under handedly skirts around Enlil instead of outright opposing him.

Question: Can you give us a tutorial of the history of the fallen angels and their corruption of humans and the extraterrestrials, including a timeline for when the Anunnaki first arrived on Earth, what caused the downfall of Atlantis, what extraterrestrials were involved, and what were other major consequences for humanity of the extraterrestrial presence?

Creator’s Answer:

The Anunnaki have been on Earth for millions of years, and in fact, they were responsible for the annihilation of an earlier go-round of human creation, so this is the second attempt in current universe for the successful launch of the divine human. The Anunnaki had left the Earth for an extended period and this was used as an opportunity to reintroduce a divine human in physical form and establish them. This was indeed followed by the re-appearance of Anunnaki who detected this event intuitively, and came to investigate and see what they could exploit for themselves. This started a long saga of human suppression as they resumed their old ways in subjugating humans, to enslave them and use them as a slave labor force. And this coincided with the need at that time for some raw materials that were obtainable from the Earth and gave them a handy workforce for this purpose. This was the mining of gold, and this started approximately 150,000 years ago and continued for at least 100,000 years more. At that point, there was waning interest and they left the humans largely alone to fend for themselves, knowing they could return at any time and further exploit them.

The Arcturians and their robotic Greys entered the picture during the time of Atlantis. This was a period of great awakening of humanity in which much progress was made to extend the size of human population and to further the ascension progress of enlightenment through the recovering of autonomy and making great strides with healing the trauma from all that had happened historically. During this entire period, the fallen angels were an influence as they had been involved in the culture of the Anunnaki long before they came to Earth. So this was a thorn in the side of humans, so to speak, from the very beginning, and this was part of the early warning from Creator to humans again and again through all of the intuitive channels available.

The earliest humans had a much greater intuitive reach and were able to receive guidance with much greater clarity than typical today. So the average human would be on the lookout for signs of spirit interference and had a working knowledge of taking care of this by requesting divine help. The great change was instituted by, again, a re-visiting by Anunnaki who degraded the human genome at that point and restricted access both to higher self and to the deep subconscious level of the mind. And this was to limit the human reach once and for all, so they would be readily manageable through manipulation and would be less likely to cause trouble.

This was setting the stage for what happened in Atlantis, for the downgrade of human was creeping into their society and that of other societies, because this was done across the board and began to influence the quality of existence. And this caused much consternation and much blaming of one another, and particularly other outside groups among the world’s aggregate population. This was all fomented by spirit meddler interference and propaganda from within the mind to see enemies in anyone different, and to create high levels of discord within the human hierarchies and institutions. This set the scene to foment a major war among the two great peoples of the day, and this was aided and abetted by the Arcturians and the Arcturian Greys, as well as Reptilians who entered at that time.

It was for the purpose of carrying out an extermination that the Alliance was first formed. This was nearly successful, but was again constrained by divine intervention. And at this point, the Extraterrestrial Alliance lost their interest in finalizing things, and the reason was the curiosity of the Arcturians and especially the Arcturian Greys in further understanding the novel aspects of the divine human in seeing the immortal nature close at hand, and by following generations of humans coming and going were intrigued with possibilities of discovering the secrets of this and incorporating this within their own lineage. And so this was the way the divine realm kept open a lifeline, although the trade-off was allowing humans to become the guinea pigs for research and exploitation by the Arcturians and the Arcturian Greys in studying the human genome.

This experiment was nearly eradicated by the war at that point, but has continued to this day and has become, in some ways, a liability for the Extraterrestrial Alliance, as the scope is so huge it commands much time and effort. The Greys are tireless, but the other entities have differing interests and are no longer wishing to support this enterprise. The power and reach of the alien Greys is such that it is not a simple matter to just shut this program down. So this will be a major challenge and is part of the shift going on in focus of the Extraterrestrial Alliance and will be a factor in determining the overall plans for humanity as to the timetable needed to wean the alien Greys away from their obsession with human experimentation.

All four of these extraterrestrial groups maintain a foothold here, some in quite large numbers, and their reach is vast and near total. It is only the extent to which they want to cause interference and pain directly that any human freedoms still exist as it is a kind of sport for them to interfere. So things are at a precarious point with the balance of power resting on three pillars: one being the shifting resolve of the Extraterrestrial Alliance members and how they view the future utility of maintaining humanity versus its termination; the second being the somewhat weakened resolve of humans to focus on their further enlightenment, which makes them more in alignment with annihilation than rescue; and then the third pillar being the divine realm who remain steadfast in pursuing a full enlightenment of the divine human, but awaiting the outcome of what is chosen by all the stakeholders involved, as it remains an experiment and a contest among the physical stakeholders to determine the future of each party and how they might interact with one another.

This is why humans themselves have a critical role in their future beyond the mundane attendance to their creature comforts, and economic stability, and governmental efficiency, and the diplomatic interaction with other nation-states, and so on. The wildcard in the future of humanity lies with the Extraterrestrial Alliance and whether they can be the final determinant for a positive versus a negative outcome. The spirit meddlers cannot help themselves in promoting depravity, for it is who they are, even though this is perilous in the end for them because if they lose their physical hosts they will perish as well. But they are not capable of seeing things in this way and recognizing alternatives to save themselves. This is why human alone can apply reason and wisdom, if knowledgeable about the true meaning of what is at stake and the facts at hand and the options available.

We have been proposing again and again, that all reach out to the divine light for support and continued help for all levels of human endeavor. This is the answer needed—to strengthen the second of the three pillars and embrace the third pillar that is weakened and will continue to weaken with respect to helping humanity or allowing suffering. The humans can change that if they desire it to happen, and the divine realm can make it so. It is simply a choice, but humans need to weigh in with their vote and do so consciously, not necessarily with full understanding of the history and the details as we have outlined things with at least a broad brush, but truly wanting in their hearts to be partners with Creator in bringing in love for all, to raise up humanity to ever-greater heights. If enough humans do so, this will happen, and for all involved.

How does the Neanderthals tie in to this?

Remember, the Torah was never claimed to be “older” than the Sumerian documents. That doesn’t make it untrue, however. The Hebrews had been in Egypt for 300 years before Moses transcribed the Genesis story, meaning they could only have gleaned a borrowed myth from the Egyptians.

Abraham was in Babylon during Asshur’s (Nimrod) reign, but left to settle in Canaan after some trouble there. So it is possible that through Abraham was preserved a creation myth that was passed down all the way to Moses, but it is also possible that God actually revealed to Moses an untainted account of creation. The Hebrew scriptures are, after all, less confusing and less metaphorical than just about any other myths.

Just because something was written down earlier, that doesn’t mean it represents the most accurate account.

Well said Patrick.

In the Bible in order to make an apparent monotheism they reduced actions made by many gods all in one god, and so actions that made Enlil (but not only) like the flood for example, in the Bible are committed only by Yahweh, but Yahweh was mainly the one that contacted Giacobbe and Moses that as epithet had “Lord of the mountain” and that one was Ish.kur(Enlil’s son). KUR in Sumerian means “mountain” whereas ISH is a play on words that comes from uniting the ISHA Akkadian (lord) with the Canaanite ending ISH (mountain), the glyph that is translated into Akkadian with SHADDU, and that will evolve into Hebrew in El Shaddai, where El means “Lord”, while Shaddai means “mountain”.

“….the downgrade of human was creeping into their society and that of other societies, because this was done across the board and began to influence the quality of existence. And this caused much consternation and much blaming of one another, and particularly other outside groups among the world’s aggregate population. This was all fomented by spirit meddler interference and propaganda from within the mind to see enemies in anyone different, and to create high levels of discord within the human hierarchies and institutions.”

Ahem, does the above rings a bell?

I appreciate all the theorization here, and I think some broad Truth can be gleaned.

However, there seems to be confusion as to Enlil’s and Enki’s identities as regards Yahweh and Lucifer.

The overall narrative places new meaning upon, and introduces many questions regarding the Old Testament and the motives of Yahweh. Sometimes Yahweh (Enlil? Enki? Or a combination?) embodied love, but at other times genocide and an infantile temper.

Yet that wouldn’t rule out a Creator of ALL, including the Creator of Enlil and Enki, Yahweh (whoever he was) and Lucifer (whoever he was).

It’s my opinion that Jesus Christ came representing our Creator with His message of Grace, Salvation, and Divine respite from this epic waring of the sub-gods, with their corruption and infantile tendencies.

A picture is emerging, but there are lots of details we’re not (or at least I”M not) yet privy to.

I wish all of you the best.

Correction: ring a bell, not “rings” a bell! Arg!

“”A picture is emerging, but there are lots of details we’re not (or at least I”M not) yet privy to.”

Dr. Joseph P. Farrell has researched this subject extensively and brilliantly. His observations and conclusions might be interesting to anyone seeking to dig deeper.

all these stories and myths are fascinating! ive been binge reading about all this for hours now. thank you all for sharing your knowledge!

this site is gold (anunnaki pun intended), thank you for creating it!

Gold is an abundant element in the universe; they could’ve get it from nearby rocks/planets.

So they must have come here looking for something else, something that is rare, something that’s a common currency for all advanced civilisations capable of interstellar travel.

That something can be only one thing: fuel for interstellar space ships;

the kyber crystals ( yes.., the ones powering Jedi’s lightsabers, ships, Death Star etc)

We know that only 5% of Earth’s crust is carbon based.

Most of Earth’s mass (95%) is silicone based (quartz) stuff.

Why?

Because this planet/”rock” was/(and still is!) in fact a gigantic silicone-based civilisation (Avatar like) where all the “silica trees” and silica “mushrooms” were super-intelligent and also gigantic in size (100Km tall).

These intelligent “trees” were/(are) capable to synthesize (at the atomic level, like a 3D printer) anything they imagined (through their fruits.. so you they can embed knowledge in an apple so to be trasfered to a human through simple ingestion; literally eating knowledge!!!); even carbon based life.

Silicone based life doesn’t need oxygen, heat or any other special conditions to grow and they never die.

Silicon based intelligence populated the entire universe long before (billions of years) they decided to create/synthesize something else, the first carbon based creatures (us ; yes! they created us!).

That’s why we still reffer to them as ‘The trees of knowledge’ !

These silica “trees”/entities sometimes develop/grow on their roots/veins a kind of super crystal, THE KYBER crystal; and much like our expensive carbon-based truffles, these kyber crystals are very rare and very expensive becase they can power space ships (thus help carbon base creatures now to colonize/subdue the universe)

And that’s why they came here, for the FUEL and that’s why the God from the bible cut down (killed) all these intelligent giantic “trees”:

e.g. Ezekiel 31:3 , Daniel 4:13-23